Wednesday, October 25, 2006

more from Xi'an

Last week I talked about Xi’an as the center of the first unified Chinese dynasty about two and a half centuries ago. After the fall of the Qin dynasty, China sustained periods of warring states followed by repeated attempts to establish unifying dynasties. China also has a history of invasions from the north by Mongols who periodically ruled the Yellow River basin. The Great Wall was constructed over the course of several dynasties in a futile effort to block these northern invaders.

One of the more successful Mongol rulers was Kublai Khan who ruled Mongolia and the Yellow River basin of China in the latter half of the thirteenth century. In 1269 the Italian explorer Marco Polo returned from a commercial trip to China with letters from the Khan to the Pope asking that western intellectuals be sent to his court to teach them about the West. The return trip of Marco Polo, which lasted almost twenty five years, is described in his famous book, Travels, reportedly dictated by Polo from a prison cell. While there is substantial debate about the veracity of Polo’s book, there is little question that the reported adventures popularized in the West what was known as the Silk Road—one of the greatest commercial routes in world history.

Initially established in the Dark Ages, the Silk Road created overland commercial ties between Europe and China centuries before maritime contacts were established. The Road, which stretches from the Mediterranean to China, passes through what is today Turkey or Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan to the famous Khyber Pass over the Himalayans. The Khyber Pass lies between modern Afghanistan and Pakistan and continues to be a major commercial route for smugglers of cocaine, terrorists, and anything else of value. From Pakistan the Road leads into Tibet, across the Kobi desert, and into the Yellow River basin. There, Xi’an was the major terminal and trading center of this commercial route.

Trade on the Silk Road brought Europe scarce and exotic goods including silk, jade, pepper and other spices, and eastern technology such as the manufacture of gunpowder. It is curious that the Chinese invention of moveable type and the printing press never made it back to the West—not terribly important I guess. While goods flowed freely on the backs of numerous camel caravans, an equally important flow of people, their cultures, and their religions passed from region to region. As one would expect, the rise of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries was carried along the Silk Road into China.

As a consequence of this early commercial contact, Xi’an today has a large Muslim population descended from the early merchants. They speak Chinese, but still cling to the very open practice of Islam. They are racially distinct and many use traditional dress. Today, many of these descendants are active merchants in Xi’an and throughout China—particularly in the western provinces.

In the center of Xi’an, not far from the Bell Tower, is the ancient, central Mosque. It is a beautiful and serene place that actively serves the spiritual needs of the local population. Around the Mosque for blocks in any direction is a traditional Arab market or bazaar with narrow alleys, crowded shops, and every variety of exotic food imaginable. Particularly popular are sweets (candies and pastries), and dried fruits (dates, nuts) that in an earlier time came over thousands of miles by camel caravan from unknown western lands.

The Mosque and the Muslim quarter are of interest to both foreign tourists and local Chinese tourists. There were lines of Chinese outside of one shop waiting to buy a popular fried pastry prepared in an open air shop by Muslims in typical costume (photo). As we walked around, we passed one section of the market that seemed to be the liver section. We must have passed at least twenty shops, each of which had ten to twenty beef livers stacked up, uncooled in the front of the stores. They must have been smoked or preserved in some other fashion. I have no idea where all of that liver ends up in the food chain (and I hope I never find out).

The palpable feel of the historic Silk Road in the Arab quarter of Xi’an was fascinating. I almost expected Marco Polo or Kubli Kahn to step out around the next little alleyway and offer to exchange some European industrial good for silk or spices. After all, that was just yesterday in Chinese time—only several hundred years before Columbus bumped into a land mass that prohibited him from reaching the East Indies as he searched for an alternative to the Silk Road.

Back home in Beibei we found that little had changed. Our favorite noodle restaurant is still in business. It is operated by a very nice Muslim family. The wall decorations include a large picture of the Grand Mosque during the Hajj. Mom and Dad run the place and their children work as servers in between classes at the University. Their daughter is studying Food Science and one son is in Engineering. They serve no pork, but just about everything else. They, and some other Muslim merchants in town, remind us how far west we really are here in Beibei and how quickly we can step back in time.

One of the more successful Mongol rulers was Kublai Khan who ruled Mongolia and the Yellow River basin of China in the latter half of the thirteenth century. In 1269 the Italian explorer Marco Polo returned from a commercial trip to China with letters from the Khan to the Pope asking that western intellectuals be sent to his court to teach them about the West. The return trip of Marco Polo, which lasted almost twenty five years, is described in his famous book, Travels, reportedly dictated by Polo from a prison cell. While there is substantial debate about the veracity of Polo’s book, there is little question that the reported adventures popularized in the West what was known as the Silk Road—one of the greatest commercial routes in world history.

Initially established in the Dark Ages, the Silk Road created overland commercial ties between Europe and China centuries before maritime contacts were established. The Road, which stretches from the Mediterranean to China, passes through what is today Turkey or Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan to the famous Khyber Pass over the Himalayans. The Khyber Pass lies between modern Afghanistan and Pakistan and continues to be a major commercial route for smugglers of cocaine, terrorists, and anything else of value. From Pakistan the Road leads into Tibet, across the Kobi desert, and into the Yellow River basin. There, Xi’an was the major terminal and trading center of this commercial route.

Trade on the Silk Road brought Europe scarce and exotic goods including silk, jade, pepper and other spices, and eastern technology such as the manufacture of gunpowder. It is curious that the Chinese invention of moveable type and the printing press never made it back to the West—not terribly important I guess. While goods flowed freely on the backs of numerous camel caravans, an equally important flow of people, their cultures, and their religions passed from region to region. As one would expect, the rise of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries was carried along the Silk Road into China.

As a consequence of this early commercial contact, Xi’an today has a large Muslim population descended from the early merchants. They speak Chinese, but still cling to the very open practice of Islam. They are racially distinct and many use traditional dress. Today, many of these descendants are active merchants in Xi’an and throughout China—particularly in the western provinces.

In the center of Xi’an, not far from the Bell Tower, is the ancient, central Mosque. It is a beautiful and serene place that actively serves the spiritual needs of the local population. Around the Mosque for blocks in any direction is a traditional Arab market or bazaar with narrow alleys, crowded shops, and every variety of exotic food imaginable. Particularly popular are sweets (candies and pastries), and dried fruits (dates, nuts) that in an earlier time came over thousands of miles by camel caravan from unknown western lands.

The Mosque and the Muslim quarter are of interest to both foreign tourists and local Chinese tourists. There were lines of Chinese outside of one shop waiting to buy a popular fried pastry prepared in an open air shop by Muslims in typical costume (photo). As we walked around, we passed one section of the market that seemed to be the liver section. We must have passed at least twenty shops, each of which had ten to twenty beef livers stacked up, uncooled in the front of the stores. They must have been smoked or preserved in some other fashion. I have no idea where all of that liver ends up in the food chain (and I hope I never find out).

The palpable feel of the historic Silk Road in the Arab quarter of Xi’an was fascinating. I almost expected Marco Polo or Kubli Kahn to step out around the next little alleyway and offer to exchange some European industrial good for silk or spices. After all, that was just yesterday in Chinese time—only several hundred years before Columbus bumped into a land mass that prohibited him from reaching the East Indies as he searched for an alternative to the Silk Road.

Back home in Beibei we found that little had changed. Our favorite noodle restaurant is still in business. It is operated by a very nice Muslim family. The wall decorations include a large picture of the Grand Mosque during the Hajj. Mom and Dad run the place and their children work as servers in between classes at the University. Their daughter is studying Food Science and one son is in Engineering. They serve no pork, but just about everything else. They, and some other Muslim merchants in town, remind us how far west we really are here in Beibei and how quickly we can step back in time.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

A Visit to Xi’an

In 1900 that most populous city in Florida was Key West. In other words, most of what we know about Florida has happened in the past century. A short walk from our apartment in Beibei leads to top of a small river ravine that has been inhabited and farmed for the past 5,000 years. With the adoption of agriculture to replace the hunting and gathering societies, came the need for some form of social organization. As agrarian societies developed, labor specialization became common. Some folks were farmers and others were merchants, priests, sheriffs, or tribal chiefs. These small societies were held together by a common belief, common ancestry, and/or the power of the local chiefs. That power usually manifested itself in some form of a military unit capable of protecting the existing chiefdom, or, in many cases, expanding it through conquest.

Early Chinese history is an ever changing collage of rival chiefdoms rising and falling with the passing of time. Until fairly recently (by Chinese standards) China as a single country did not exist—it was simply a collection of numerous chiefdoms or, to use common phraseology today, warlords. The political organization that existed over the land mass of China looked a lot like what we see in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, or Iraq today—a shifting pattern of local warlords with no effective central government.

The first successful unification of the many chiefdoms or city-states along the Yellow River basin was in 221B.C. by a young ruler of the Qin state named Shi Huangdi. Many of the chiefdoms along the Yangtze River were also brought under the central control of what became known as the Qin {pronounced CHIN} dynasty—the first in Chinese history. The geographic center of the Qin dynasty was Xi’an {SHEE-enh}—a rich agricultural center on the Yellow River. As the Qin consolidated power, Shi proclaimed himself the first Emperor of China. During the centralization of the Qin dynasty the Chinese language and writing were standardized and part of the Great Wall was built to defend against raiders from the north.

During the first week of October the mid-autumn festival holiday was celebrated and classes at Southwest University were suspended for a week. My wife and I took advantage of the holiday to visit Xi’an which today is one of the most popular tourist attractions in China, both for Chinese tourists and foreign tourists like us.

Today Xi’an is a booming metropolitan center of about 7 million people. For the most part, in spite of its historic past, it is a young city with broad boulevards laid out to accommodate motorized traffic. It seems to be growing rapidly with construction projects everywhere. In addition, it is preparing to be one of the regional sites of the 2008 Olympics. We flew from a very modern airport in Chongqing (an old city on the Yangtze) to a very modern airport in Xi’an (an old city on the Yellow) in about an hour. We left Chongqing through an incredible cloud of air pollution and arrived in Xi’an in an equally dense cloud of pollution. Because of the irritating, consistent, and apparently pervasive air pollution, we never saw our shadows during four days at Xi’an.

We stayed in the center of the old city of Xi’an. From our hotel window we could see the Bell Tower on the central plaza (see photo and note air pollution). The old city was enclosed with a wall and moat. The entire old wall still exists. The adventurous tourist can rent a bicycle and ride the entire 14 kilometer circumference on top of the wall. The old city is entered by four gates in the four directions with roads that lead to the Bell Tower.

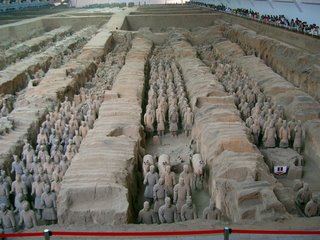

The primary tourist attraction in Xi’an is the tomb built by Emperor Shi for his eventual burial. The tomb contains some 6,000 terra cotta warriors (instead of sacrificed human warriors) who silently stand guard over an area about the size of three football fields. Only a portion of the entire tomb has been excavated and reconstructed. The sheer size (and audacity) of the tomb is overpowering (see photo). The tomb, first discovered in the 1970’s has been featured on the cover of National Geographic magazine and was visited by President Clinton during a state visit to China about ten years ago.

As with the modern examples of despotic consolidators such as Tito and Sadam, the unification of China was not a peaceful process. It was accomplished at a great cost in terms of human life. In the face of a superior military force and a reign of terror many local warlords lost their status and power. Nevertheless, old regional identities and the old frictions among the various warlords were never eliminated, they were merely subjugated to a stronger central power sustained by military superiority and sustained terror. Upon the death of Emperor Shi in 210 B.C., his son became the Emperor and was soon overthrown in a peasant revolt supported by the deposed warlords. The first unification of China had been brief and ended in failure.

Next week, I will discuss one other interesting aspect of Xi’an.

Early Chinese history is an ever changing collage of rival chiefdoms rising and falling with the passing of time. Until fairly recently (by Chinese standards) China as a single country did not exist—it was simply a collection of numerous chiefdoms or, to use common phraseology today, warlords. The political organization that existed over the land mass of China looked a lot like what we see in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, or Iraq today—a shifting pattern of local warlords with no effective central government.

The first successful unification of the many chiefdoms or city-states along the Yellow River basin was in 221B.C. by a young ruler of the Qin state named Shi Huangdi. Many of the chiefdoms along the Yangtze River were also brought under the central control of what became known as the Qin {pronounced CHIN} dynasty—the first in Chinese history. The geographic center of the Qin dynasty was Xi’an {SHEE-enh}—a rich agricultural center on the Yellow River. As the Qin consolidated power, Shi proclaimed himself the first Emperor of China. During the centralization of the Qin dynasty the Chinese language and writing were standardized and part of the Great Wall was built to defend against raiders from the north.

During the first week of October the mid-autumn festival holiday was celebrated and classes at Southwest University were suspended for a week. My wife and I took advantage of the holiday to visit Xi’an which today is one of the most popular tourist attractions in China, both for Chinese tourists and foreign tourists like us.

Today Xi’an is a booming metropolitan center of about 7 million people. For the most part, in spite of its historic past, it is a young city with broad boulevards laid out to accommodate motorized traffic. It seems to be growing rapidly with construction projects everywhere. In addition, it is preparing to be one of the regional sites of the 2008 Olympics. We flew from a very modern airport in Chongqing (an old city on the Yangtze) to a very modern airport in Xi’an (an old city on the Yellow) in about an hour. We left Chongqing through an incredible cloud of air pollution and arrived in Xi’an in an equally dense cloud of pollution. Because of the irritating, consistent, and apparently pervasive air pollution, we never saw our shadows during four days at Xi’an.

We stayed in the center of the old city of Xi’an. From our hotel window we could see the Bell Tower on the central plaza (see photo and note air pollution). The old city was enclosed with a wall and moat. The entire old wall still exists. The adventurous tourist can rent a bicycle and ride the entire 14 kilometer circumference on top of the wall. The old city is entered by four gates in the four directions with roads that lead to the Bell Tower.

The primary tourist attraction in Xi’an is the tomb built by Emperor Shi for his eventual burial. The tomb contains some 6,000 terra cotta warriors (instead of sacrificed human warriors) who silently stand guard over an area about the size of three football fields. Only a portion of the entire tomb has been excavated and reconstructed. The sheer size (and audacity) of the tomb is overpowering (see photo). The tomb, first discovered in the 1970’s has been featured on the cover of National Geographic magazine and was visited by President Clinton during a state visit to China about ten years ago.

As with the modern examples of despotic consolidators such as Tito and Sadam, the unification of China was not a peaceful process. It was accomplished at a great cost in terms of human life. In the face of a superior military force and a reign of terror many local warlords lost their status and power. Nevertheless, old regional identities and the old frictions among the various warlords were never eliminated, they were merely subjugated to a stronger central power sustained by military superiority and sustained terror. Upon the death of Emperor Shi in 210 B.C., his son became the Emperor and was soon overthrown in a peasant revolt supported by the deposed warlords. The first unification of China had been brief and ended in failure.

Next week, I will discuss one other interesting aspect of Xi’an.

Holidays

China has three major holiday seasons. The smallest and least significant is May Day on the first of May. This is the traditional Labor Day in Communist countries. The largest and most significant is New Year’s Day. Unlike New Year’s Day in the U.S. which is tied to our Gregorian calendar, New Year’s in China is tied to the lunar calendar (see any placemat in a Chinese restaurant). New Year’s usually comes in late January and is cause for several weeks of celebration including the break between semesters at the universities.

The third holiday season includes the fall holidays of National Day and the Mid-Autumn Festival. National Day is the first of October and celebrates the creation of a unified China under the communist regime of Mao Zedong in 1949. National Day is the equivalent of our 4th of July. This year National Day fell on a Sunday. Saturday night we heard, but did not see, a fireworks display in Beibei. The next day we wandered about campus and noted that the campus post office and numerous campus banks were open. About the only thing different from any other Sunday was that all buses were decorated with crossed Chinese flags on their windshields. In short, National Day is not much of a celebration.

The Mid-Autumn Festival is another matter. This holiday is tied to the lunar calendar—it is celebrated on the full moon of the eighth lunar month. This year it fell on Oct. 6 (Friday). Most societies have some form of harvest festival—Thanksgiving in the U.S. and Canada—and in China it is the Mid-Autumn Festival. It is a time for families to get together, tell stories, and eat traditional foods. As a result, there is a lot of travel with intense congestion at travel depots. For instance, we had to wait for an hour to get a bus out of Beibei—usually there is no wait at all.

The mid-autumn full moon is the biggest, brightest full moon of the year—we call it the harvest moon. We sing about it, but we do not formally celebrate it. In China families gather on the night of the full moon and exchange gifts (usually moon cakes) as a sign of familial love. If family members are unable to be together, they can look at the full moon and know that their loved ones are doing the same so the bond of love is shared in the moment of the full moon.

As with most family-centered celebrations, kids are very important. We saw many girls in the 5-10 year old category dressed up in moon-goddess costumes including little headdresses with many sparkles on them. Also popular are balloons (for the younger set) in the obvious shape of a full-moon.

Among the adults, the two most popular gifts are moon cakes and fruit. The Southwest University gave each employee, including my wife and me, a gift box of moon cakes and a carton (the size of a ream of paper) of fresh pears. We had a hard time unloading two cartons of pears as no one could understand why we would want to give away so precious a gift.

To fully understand moon cakes one must be aware of a significant difference between American cooking methods and those of China (and Asia in general). Kitchens here, in restaurants and in homes, do not have ovens. As a consequence, breads and cakes (not to mention Thanksgiving turkeys) are very scarce and something of a luxury. There is one company that serves Beibei with baked goods in very fancy franchise stores with relatively high prices. At these stores we can buy breakfast rolls, bread (sometimes), and cookies. Cakes are a special order item and are purchased for weddings, birthdays, and the like. Consequently, eating moon cakes, or baked pastries, to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival is a big deal. These small cakes vary in size from a hockey puck up to a 5x2-inch circular cake. They are (as are all baked goods in China) very sweet and are frequently stuffed with fruits or meats. The real classic moon cake has a boiled egg yolk stuffed inside of it that looks just like the full moon. For those of modest incomes, you can get unleavened moon cakes that are about the size of an Oreo cookie and are mostly lard and flour.

About two weeks ago stores started stocking up on moon cakes. They were everywhere. The most popular presentation is a fancy gift box with an assortment of different moon cakes (see photo, this is what SWU gave us). As you look at people traveling for the holidays, many are carrying one or more gift boxes of moon cakes and/or fruit to their destinations. Frankly, I don’t know how all of the moon cakes are ever going to be eaten and I expect there are a number of Chinese children with sore tummies on the morning after the night before.

According to a newscast on the eve of the Mid-Autumn Festival, in years past moon cake gift boxes included a bottle of whiskey or wine which made the gift boxes very expensive as a good bottle of whiskey can run $50 and up. This year the government has outlawed this practice so the gift boxes would be cheaper and available to a wider range of consumers. There was no hint in the broadcast that temperance had anything to do with the new government rules. In any case, the celebration continued although in Beibei it rained all night and we were unable to see the moon—unrequited love.

The third holiday season includes the fall holidays of National Day and the Mid-Autumn Festival. National Day is the first of October and celebrates the creation of a unified China under the communist regime of Mao Zedong in 1949. National Day is the equivalent of our 4th of July. This year National Day fell on a Sunday. Saturday night we heard, but did not see, a fireworks display in Beibei. The next day we wandered about campus and noted that the campus post office and numerous campus banks were open. About the only thing different from any other Sunday was that all buses were decorated with crossed Chinese flags on their windshields. In short, National Day is not much of a celebration.

The Mid-Autumn Festival is another matter. This holiday is tied to the lunar calendar—it is celebrated on the full moon of the eighth lunar month. This year it fell on Oct. 6 (Friday). Most societies have some form of harvest festival—Thanksgiving in the U.S. and Canada—and in China it is the Mid-Autumn Festival. It is a time for families to get together, tell stories, and eat traditional foods. As a result, there is a lot of travel with intense congestion at travel depots. For instance, we had to wait for an hour to get a bus out of Beibei—usually there is no wait at all.

The mid-autumn full moon is the biggest, brightest full moon of the year—we call it the harvest moon. We sing about it, but we do not formally celebrate it. In China families gather on the night of the full moon and exchange gifts (usually moon cakes) as a sign of familial love. If family members are unable to be together, they can look at the full moon and know that their loved ones are doing the same so the bond of love is shared in the moment of the full moon.

As with most family-centered celebrations, kids are very important. We saw many girls in the 5-10 year old category dressed up in moon-goddess costumes including little headdresses with many sparkles on them. Also popular are balloons (for the younger set) in the obvious shape of a full-moon.

Among the adults, the two most popular gifts are moon cakes and fruit. The Southwest University gave each employee, including my wife and me, a gift box of moon cakes and a carton (the size of a ream of paper) of fresh pears. We had a hard time unloading two cartons of pears as no one could understand why we would want to give away so precious a gift.

To fully understand moon cakes one must be aware of a significant difference between American cooking methods and those of China (and Asia in general). Kitchens here, in restaurants and in homes, do not have ovens. As a consequence, breads and cakes (not to mention Thanksgiving turkeys) are very scarce and something of a luxury. There is one company that serves Beibei with baked goods in very fancy franchise stores with relatively high prices. At these stores we can buy breakfast rolls, bread (sometimes), and cookies. Cakes are a special order item and are purchased for weddings, birthdays, and the like. Consequently, eating moon cakes, or baked pastries, to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival is a big deal. These small cakes vary in size from a hockey puck up to a 5x2-inch circular cake. They are (as are all baked goods in China) very sweet and are frequently stuffed with fruits or meats. The real classic moon cake has a boiled egg yolk stuffed inside of it that looks just like the full moon. For those of modest incomes, you can get unleavened moon cakes that are about the size of an Oreo cookie and are mostly lard and flour.

About two weeks ago stores started stocking up on moon cakes. They were everywhere. The most popular presentation is a fancy gift box with an assortment of different moon cakes (see photo, this is what SWU gave us). As you look at people traveling for the holidays, many are carrying one or more gift boxes of moon cakes and/or fruit to their destinations. Frankly, I don’t know how all of the moon cakes are ever going to be eaten and I expect there are a number of Chinese children with sore tummies on the morning after the night before.

According to a newscast on the eve of the Mid-Autumn Festival, in years past moon cake gift boxes included a bottle of whiskey or wine which made the gift boxes very expensive as a good bottle of whiskey can run $50 and up. This year the government has outlawed this practice so the gift boxes would be cheaper and available to a wider range of consumers. There was no hint in the broadcast that temperance had anything to do with the new government rules. In any case, the celebration continued although in Beibei it rained all night and we were unable to see the moon—unrequited love.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Sichuan Hot Pot

Beibei is administratively part of the municipality of Chongqing. This municipality, like Washington, D.C., is a federal entity that is independent of any provincial government. There are currently four such municipalities in China, Beijing and Shanghai being two of the better known ones. Prior to the creation of the municipality of Chongqing, Beibei was part of the province (c.f., state) of Sichuan.

In ancient times, most of the economic and political development of China was located in western valleys of the two main river systems in China—the Yellow (in the north) and the Yangtze (in the south). Sichuan is located in the heart of the Yangtze River basin which is similar to our Mississippi river basin except it flows in a west to east direction instead of north to south. Shanghai, a major international port, is at the mouth of the Yangtze and is analogous to New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Sichuan is a vast region that is traditionally rural and agricultural. With industrialization, the economic centers of the country have sifted from the western agrarian regions of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers to the eastern, coastal metropolitan areas that are closer to international markets. Much of the early history of China is of conflict between the north and south (the two river basins); much of the history of the past century has been between the east (industrial) and west (agrarian). With these economic changes, Sichuan has become one of the poorest regions of China, not unlike the upper reaches of the Mississippi River valley in eastern Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

As with any large country, China has very significant regional differences in dialect, customs, and cuisine. When Americans think about southern cuisine they think about grits, corn bread, and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. When Chinese think about Sichuan cuisine, they think about “hot pot”, and with good reason. Hot pot does not refer to a dish or type of dish, but instead to an eating format or style. Many restaurants in Beibei are hot pot. If you go to a hot pot restaurant, you will eat hot pot style. In many ways, hot pot is similar to fondue in the U.S. A large caldron, usually filled with oil, is placed over a burner at the table and raw ingredients are brought to the table. The customer, at his or her leisure, puts the ingredients into the oil to cook. When cooked, you haul the food out with your chopsticks and eat it. There is no limit as to what ingredients you may put into the hot pot. All sorts of meat are common, including fish. Veggies are also common ingredients in hot pot. These range from chunks of turnips, beans, squashes, greens, and even lettuce.

A typical “pot” is a wok shaped steel bowl that is about 18 inches in diameter with two or three quarts of liquid in it. The contents of the hot pot vary from restaurant to restaurant and customer to customer. The most basic hot pot is just a pot of oil. More common is oil with some added goodies such as a celery stalk and onions to impart some flavor to the oil. One place we visited tossed a few ham hocks into the oil that initially added some nice pork fat to the oil and by the end of the meal yielded some pretty good pieces of well cooked pork. The regional favorite is to add some peppers and spices to the oil such that everything that comes out of the pot is hot and spicy—this is really good and is the most “typical” variety of hot pot. For those not inclined to so much oil, you can also do hot pot with chicken or beef stock. With any of the above foundations in the pot, the choice of what to cook is up to the customer.

Hot pot as an eating style is a leisurely endeavor. The heat from the pot not only cooks the food, it also warms up the customers. Up-scale hot pot restaurants are air conditioned, but the locals seem to prefer open air hot pots. With the hot air and hot (and frequently spicy) food, great quantities of beverage are normally consumed with hot pot.

Hot pot is usually a social occasion. It is not something for the casual customer just looking for a quick, easy meal. Many hot pot restaurants are up-scale places where you might have a wedding reception or a similar large party. In Beibei, most up-scale restaurants are exclusively hot pot restaurants. You pay a flat rate for the pot (depending on size and contents) with an additional charge for each ingredient added to the pot. The extras are ordered and brought to the table throughout the meal. A hot pot for four in the student ghetto starts at about $1.00 per person for the pot. Elegant hot pots start at the $4.00 per person range and can go much higher. Everything in between is available.

Should you visit Beibei, your hosts will invariably take you to a hot pot meal. For the timid, it is possible to order a split hot pot in which one part has just oil and the other part has oil with peppers, and spices. One of my local friends here calls this arrangement “husband and wife” hot pot.

Some American students who are studying at Southwest University report that there is a hot pot restaurant in the Minneapolis area. There may be some others in major metropolitan areas around the country. If you want a leisurely, interesting dining experience I encourage you to try out a hot pot.

In ancient times, most of the economic and political development of China was located in western valleys of the two main river systems in China—the Yellow (in the north) and the Yangtze (in the south). Sichuan is located in the heart of the Yangtze River basin which is similar to our Mississippi river basin except it flows in a west to east direction instead of north to south. Shanghai, a major international port, is at the mouth of the Yangtze and is analogous to New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Sichuan is a vast region that is traditionally rural and agricultural. With industrialization, the economic centers of the country have sifted from the western agrarian regions of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers to the eastern, coastal metropolitan areas that are closer to international markets. Much of the early history of China is of conflict between the north and south (the two river basins); much of the history of the past century has been between the east (industrial) and west (agrarian). With these economic changes, Sichuan has become one of the poorest regions of China, not unlike the upper reaches of the Mississippi River valley in eastern Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

As with any large country, China has very significant regional differences in dialect, customs, and cuisine. When Americans think about southern cuisine they think about grits, corn bread, and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. When Chinese think about Sichuan cuisine, they think about “hot pot”, and with good reason. Hot pot does not refer to a dish or type of dish, but instead to an eating format or style. Many restaurants in Beibei are hot pot. If you go to a hot pot restaurant, you will eat hot pot style. In many ways, hot pot is similar to fondue in the U.S. A large caldron, usually filled with oil, is placed over a burner at the table and raw ingredients are brought to the table. The customer, at his or her leisure, puts the ingredients into the oil to cook. When cooked, you haul the food out with your chopsticks and eat it. There is no limit as to what ingredients you may put into the hot pot. All sorts of meat are common, including fish. Veggies are also common ingredients in hot pot. These range from chunks of turnips, beans, squashes, greens, and even lettuce.

A typical “pot” is a wok shaped steel bowl that is about 18 inches in diameter with two or three quarts of liquid in it. The contents of the hot pot vary from restaurant to restaurant and customer to customer. The most basic hot pot is just a pot of oil. More common is oil with some added goodies such as a celery stalk and onions to impart some flavor to the oil. One place we visited tossed a few ham hocks into the oil that initially added some nice pork fat to the oil and by the end of the meal yielded some pretty good pieces of well cooked pork. The regional favorite is to add some peppers and spices to the oil such that everything that comes out of the pot is hot and spicy—this is really good and is the most “typical” variety of hot pot. For those not inclined to so much oil, you can also do hot pot with chicken or beef stock. With any of the above foundations in the pot, the choice of what to cook is up to the customer.

Hot pot as an eating style is a leisurely endeavor. The heat from the pot not only cooks the food, it also warms up the customers. Up-scale hot pot restaurants are air conditioned, but the locals seem to prefer open air hot pots. With the hot air and hot (and frequently spicy) food, great quantities of beverage are normally consumed with hot pot.

Hot pot is usually a social occasion. It is not something for the casual customer just looking for a quick, easy meal. Many hot pot restaurants are up-scale places where you might have a wedding reception or a similar large party. In Beibei, most up-scale restaurants are exclusively hot pot restaurants. You pay a flat rate for the pot (depending on size and contents) with an additional charge for each ingredient added to the pot. The extras are ordered and brought to the table throughout the meal. A hot pot for four in the student ghetto starts at about $1.00 per person for the pot. Elegant hot pots start at the $4.00 per person range and can go much higher. Everything in between is available.

Should you visit Beibei, your hosts will invariably take you to a hot pot meal. For the timid, it is possible to order a split hot pot in which one part has just oil and the other part has oil with peppers, and spices. One of my local friends here calls this arrangement “husband and wife” hot pot.

Some American students who are studying at Southwest University report that there is a hot pot restaurant in the Minneapolis area. There may be some others in major metropolitan areas around the country. If you want a leisurely, interesting dining experience I encourage you to try out a hot pot.